|

The

east castle is 110 east of Palmyra; the west one is 90 to west; the

purpose of the two desert castle complexes (Qasr al-Heir Ease and West)

has stimulated much debate in recent decades. In "City in the Desert".

Recording the results of an American expedition of 1964 - 72, Grabar

note that the monumental facades of these two palaces are not

commensurate with the more mundane internal structure and the

utilitarian nature of most of the items found. Archaeologists see a

confusion of styles - Byzantine, Mesopotamian/Persian and local - which

in this case resulted more in an unresolved pastiche than the triumph

of synthesis realized in the Umayyad Mosque. Nevertheless, it is a

bizarre ruin of great interest and although one should not expect

another Palmyra or even a Resafe, the one hour diversion each way is

well worthwhile. The

east castle is 110 east of Palmyra; the west one is 90 to west; the

purpose of the two desert castle complexes (Qasr al-Heir Ease and West)

has stimulated much debate in recent decades. In "City in the Desert".

Recording the results of an American expedition of 1964 - 72, Grabar

note that the monumental facades of these two palaces are not

commensurate with the more mundane internal structure and the

utilitarian nature of most of the items found. Archaeologists see a

confusion of styles - Byzantine, Mesopotamian/Persian and local - which

in this case resulted more in an unresolved pastiche than the triumph

of synthesis realized in the Umayyad Mosque. Nevertheless, it is a

bizarre ruin of great interest and although one should not expect

another Palmyra or even a Resafe, the one hour diversion each way is

well worthwhile.

The East Palace:  There are possible traces of a pre-Islamic or Byzantine origin of the

complex, citing the presence of architectural elements such as

capitals. When work commenced on the Umayyad complex (728/9 under

Caliph Hisham), it may already have been in use for oasis garden. The

water supply that made settlement possible was based on a water-course

leading from a dam at al-Qawm, 30 km to the north west. The gardens,

850 ha in extent, were surrounded by 22 km of largely mud-brick walls. There are possible traces of a pre-Islamic or Byzantine origin of the

complex, citing the presence of architectural elements such as

capitals. When work commenced on the Umayyad complex (728/9 under

Caliph Hisham), it may already have been in use for oasis garden. The

water supply that made settlement possible was based on a water-course

leading from a dam at al-Qawm, 30 km to the north west. The gardens,

850 ha in extent, were surrounded by 22 km of largely mud-brick walls.

Like the companion castle, Qasr al-Heir West (200 km west), the scale

of the Qasr (Palace) owes a good deal to the edifice complex that

marked the second half of the Umayyad dynasty, particularly under

Caliph Hisham. Traditional explanations have covered a range of

possibilities from pleasure (a hunting lodge with oasis gardens)

through practical to military. The site was probably originally built as a grandiose agricultural

settlement intended to cower and help control warring desert tribes. It

later acquired a more distinctly economic purpose with the addition of

the east building or caravanserai to encourage commercial traffic. The

original motivation for the settlement (probably around 700) was the

need to pacify the area after a series of murderous tribal wars. The

two palaces played the major role easing the connection between

Mesopotamia and Syria on the route Damascus-al

Jezira-Mesopotamia-Persia. (al Jezira is the north east area of Syria

north the Euphrates). After Hisham's Caliphate, Syria was purposefully neglected; especially

under Abbasid rule from Baghdad. The palace wasn't, however, abandoned,

there being signs that the Abbasids saw economic advantage in bringing

it to fruition, albeit on a reduced scale. The site was abandoned

permanently in the 13th century due to the damages caused by the Mongol

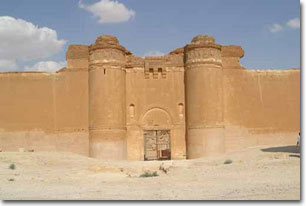

invasions. The central complex consists of two distinct castles, 40 m apart and

carefully built from fine grained grey limestone. The two gateways

guarded by semi-cylindrical towers on each side face each other with a

minaret between. The gate of the eastern castle is reasonably well

preserved and is the most interesting architectural feature of the

complex. The decoration shows a conscious juxtaposition of styles

(Mesopotamian, Byzantine and local). The two half-circle towers found

on each wall are on the entrance side moved in to flank the gateway.

The upper frieze is in brick. This smaller eastern castle (70 m²) has been judged to be the more

military in purpose, perhaps because its defenses are more intact and

it has a single entrance. It was almost certainly built as a khan or

caravanserai, possibly as an afterthought after the agriculture-based

settlement under official sponsorship had been initiated. The larger castle (167 m²) on the west had six times as much space for

habitations and common facilities but its walls and five gateways are

less well preserved. The buildings in this castle comprised twelve

segment each roughly a square - six were living quarters of

approximately the same plan; three were ancillary service areas; one

was an official building; one housed olive presses; and the last was a

mosque. The minaret, placed between the two castles, is not adequately

explained. Assumed to be contemporary with the rest of the complex, it

would be the third oldest minaret in Islam. Yet, there was no mosque to

which it was attached unless one sees it as related to the mosque in

the south eastern quarter of the larger palace. The West Castle:  The existence of a settlement in this bleak spot in the desert has

always depended on the supply of water to its gardens from the nearby

dam at Harbaqa. The water canal was 17 km long. The Palmyrene

established the first settlement here in the first century AD but it

was abandoned after their revolt in 273. The Byzantines (under

Justinian) and their local Arab allies, the Ghassanid tribe,

re-occupied the site in 559 and established a monastery, some of the

remains of which still survive. The existence of a settlement in this bleak spot in the desert has

always depended on the supply of water to its gardens from the nearby

dam at Harbaqa. The water canal was 17 km long. The Palmyrene

established the first settlement here in the first century AD but it

was abandoned after their revolt in 273. The Byzantines (under

Justinian) and their local Arab allies, the Ghassanid tribe,

re-occupied the site in 559 and established a monastery, some of the

remains of which still survive.

The Umayyad Caliphs established here a retreat from the environment and

pressures of Damascus. But this "hunting lodge" reflected the Umayyad's

Judicious cultivation of both leisure and practicality. It was built on

the Byzantine site by the last great Umayyad Caliph, Hisham (724 - 43).

The construction began almost at the same time as in the East Castle

200 km across the desert, beyond Palmyra. It served the same practical

purposes as the East Castle. Ayyūbid and Mamelukes used the site for military purposes but after the

14th century Mongol invasions, it was again deserted. The huge monumental gateway of this castle was taken to be the façade of the National Museum in Damascus. The remains of a hammam (bath) were excavated by the French. The small

reservoir for collection of the waters channeled from the Harbaqa Dam

are found to the west. From here the gardens were irrigated. A khan was

built at a distance of 1 km in 727 and its entrance has been re-erected

in the garden of the National Museum in Damascus. |